The director’s cut is a fascinating phenomenon. To some, it’s a chance to finally complete or fix a film that budget or studio troubles shuttered too early. To others… well, I’ll let Ridley Scott explain (for context, this comes from a prelude to the “director’s cut” of Alien):

“The traditional definition of the term ‘director’s cut’ suggests the restoration of a director’s original vision, free of any creative limitations… such is not the case with Alien: The Director’s Cut… I felt the original cut of Alien was perfect. I still feel that way.”

“The Original Cut”

Why am I talking about the director’s cut? Simply put, to reveal the problems with rework. Once your business whiteboard video script is complete, that’s exactly where you want to leave it. Save yourself the time, effort, and money that comes with reworking a script in production.

Let’s begin our thinking at the point of script finalization, and ask: how do you know that your script is finalized? That might sound like a question demanding a complex answer, but it really isn’t. Proofreading is vital, and reading your script aloud is useful, but there’s only one real element that ensures your script is ready: stakeholder approval.

Does legal need to review? How about relevant subject matter experts—have they had a chance to read over the script and provide feedback? Or are you, instead, simply proceeding with a script you’re pretty sure they’d approve?

Nobody wants you to get in hot water with your organization just to quickly get a script to your whiteboard artist. This is especially true of a script that is going to change, which yours almost definitely will without stakeholder approval.

Why Shouldn’t it Change?

Take every bit of care to ensure that your script does not need to change, even if this means delaying getting your script finalized for a couple of days. A strong script that doesn’t change is worth it.

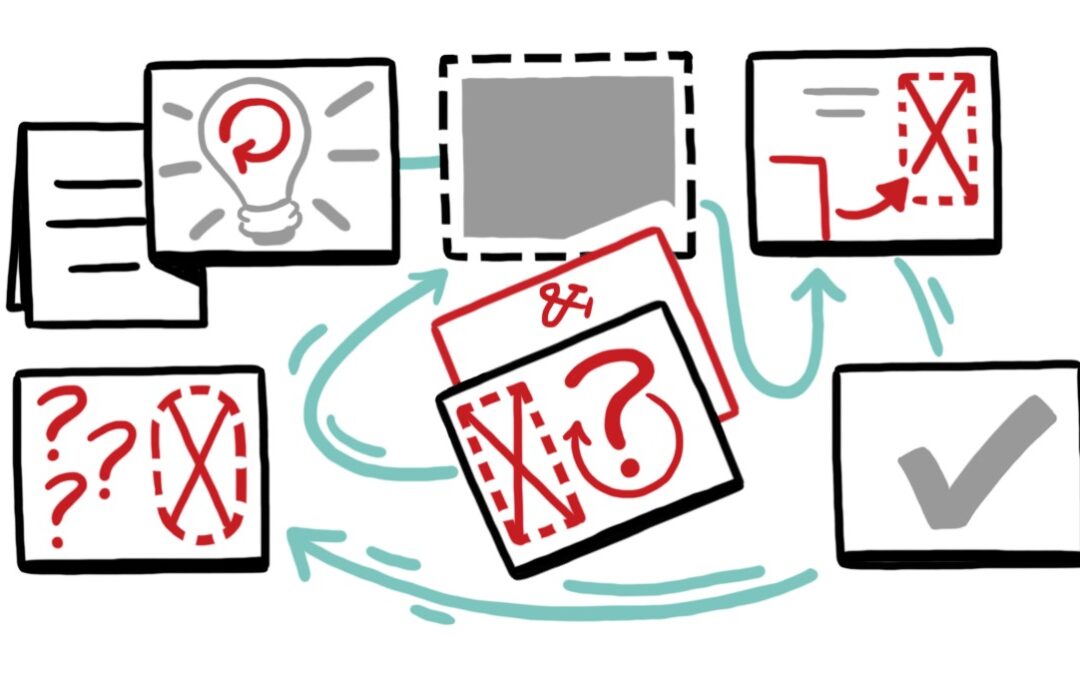

When a script changes during production, your video suffers. Since whiteboard artists create your images directly from your script, each change to the script requires a corresponding change to the drawings. Actually, I shouldn’t just say ‘corresponding,’ because depending on the scene, reworking the script could create a cascade throughout your project.

Let’s say that after creating a first round of drawings from your script, you almost entirely rewrite a scene early in the script. This necessarily changes the composition and content of the drawings of that scene—and it gets worse. What if this scene introduced a major idea, and you’re removing that idea? The effect can snowball quickly, and what seems like a single-scene adjustment can force changes in every subsequent scene.

Rework: Nobody’s Friend

Rework is not free, fast, or easy. Part of the way that whiteboard video production firms keep costs low and delivery rapid for their customers is by sticking to their process. While this process absolutely allows for revision rounds, it does not build in script rework.

Let’s clarify revision and rework for a second, because they do sound similar. Revisions are updates to existing drawings, or prior to script finalization, to language. The difference between revisions and rework is the word ‘updates,’ as opposed to ‘fully reinvents.’ Rework tears out the plumbing and knocks down a wall. Revision replaces a component with a stronger one for a specific purpose.

What’s that expression—a time for all things? Well, there is absolutely a time for script revision, and even rework if necessary: prior to delivering it, finalized, to your whiteboard video artist.

A Stitch in Time

Making sure you’ve done your due diligence, in writing and in making your writing available for review, and received all necessary signoffs before putting it into production. Your video will come together faster, review rounds will go quicker and easier, and no unexpected fees will be incurred.

Finally, consistency of composition and cohesiveness of your video will always be easier to maintain and successfully transmit to your audience when your script has carried the same messaging, in the same words, since day one. When you make a dozen changes to a script, it’s sort of like crumpling a certificate—it’s still valid, but the lines and creases are permanent.

The best-case scenario is to be Ridley Scott, needing no “director’s cut” because you were able to create the cut you wanted the first time. And it’s easy to get to this best-case scenario. Create the best video you can with a true and final script. Collaborate with your artist to update drawings in your revision rounds, and don’t create rework that will slow your video’s delivery and undercut the cohesion of a focused script.