When we evaluate the principles of Scribology, the content creation guidelines we use in our celebrated whiteboard videos, we’re always excited to see them reflected in popular media as much as our own content. We’ve looked at principled cinema, television, and more, and today, we examine the Scribology principles reflected in some of the best and most popular music videos of the last twenty years.

Voice: Justin Timberlake, “Say Something” (Feat. Chris Stapleton) (2018)

The principle of voice means articulating your message through the right narrator, whose voice conveys your meaning appropriately and effectively. In his video for “Say Something,” Justin Timberlake and featured country singer Chris Stapleton perform with seventeen other musicians and a sixty-person choir inside LA’s Bradbury Building—live, in one take. Nothing is dubbed, no edits cover mistakes; the voices and instruments the audience hears are authentically captured for the full video.

For an organic, simple song, this use of voice is perfect: free of effects and manipulation, JT, Stapleton, and their troupe are sincere, full-throated, and real. When they “say something,” the audience is hearing them mean it.

Message: Kanye West, “Jesus Walks” (2004)

Conflict, danger, salvation, loneliness, community—there’s so much in Kanye’s message in this video, it’s nearly bursting with imagery. And every frame drives home that message: spirituality can lift up anyone and everyone, even those who “feel we livin’ in hell here.” From characters in the outside world facing tribulation to the packed church in which Kanye preaches his lyrics, the audience tracks multiple narratives that all converge on this same message. “Radio needs this,” Kanye proclaims from his pulpit, and the video’s visual storytelling makes it hard to argue.

Story: Weezer, “Buddy Holly” (1994)

There are few quicker ways to transmit information than through story, our human coding language. That’s why Weezer’s “Buddy Holly” video patterned its visual story after a classic one: an “episode” of the popular program Happy Days. From Lou’s excited introduction of the band to Fonzie and other Happy Days characters dancing and interacting with the band, to the subject matter of the song itself (an ode to the titular Holly, famous in the same 1950’s universe of the show), the video uses well-known stories and figures to install Weezer in the same category of classics.

Motion: Tom Waits, “Lie to Me” (2006)

This video is a great example of taking a proven-successful design principle and putting a clever spin on it. In it, veteran singer-songwriter Tom Waits sings a short, punchy track while playing guitar, dancing, and jumping around.

Except, he doesn’t—the entire video is a series of still photographs, edited so quickly that it appears that Waits is moving. It’s a fun way to acknowledge that motion draws the eye and heightens engagement, even when that motion is manufactured through editing. The old adage that one can break the rules only once they truly know them seems to be proven here, and an old pro like Waits certainly knows the rules.

Surprise: Fatboy Slim, “Weapon of Choice” (2001)

Fatboy Slim’s “Weapon of Choice” opens as inauspiciously as a video can, when it’s starring a cultural icon like Christopher Walken: nearly silent, with the actor sitting motionless in a hotel lobby. Then, as the music kicks in, Walken’s mood picks up, and he begins to dance.

It’s certainly a surprise to watch someone apparently half-asleep snap into fantastic movement, but that’s not the only surprise—as the video goes on, his abilities seem to grow. When we see him press an elevator button without touching it, the dopamine rush that comes from being surprised hits hard. But nothing surprises us more than when Walken leaps over a second-floor railing and literally flies into the air. “Don’t be shocked by the tone of my voice,” insist the lyrics, but the video ensures that you’ll get that shock from the principle of surprise—over and over.

Image Density: Daft Punk, “Around the World” (1997)

Densely packing frames with engaging images is a hallmark of director Michel Gondry’s videos, and “Around the World” is a masterclass in the principle. In a large dance space filled with circular platforms, Gondry creates a sort of synchronized-swimming effect with dozens of costumed dancers moving in groups to the multi-instrumental track. Each group of dancers follows one part of the music (some dance to the bassline, others follow the synths, etc.), driving viewer engagement with each element of the song while creating a holistic engagement with the beat at the same time.

Motion certainly drives engagement—but little drives it more than motion spread across a room, purposefully linked to the song it reinforces.

And as for retention? Give it a watch, and try to get “Around the world, around the world” out of your head.

Sync: The Pharcyde, “Drop” (1995)

The principle of sync is defined by the matching of audio and visual elements, as a clash between the two can be potentially ruinous to audience engagement and message retention. “Drop” looks at synchronization backwards, literally: the entire video is shot in reverse, but the visuals are so carefully crafted that this approach actually takes a few seconds to register with the viewer.

What’s more, the audio-visual sync of the track and the reversed motion is meticulously mastered. Every member of the Pharcyde is literally speaking backwards, pronouncing phonemes that guaranteed that, when played in reverse, their mouths would appear to be forming the lyrics normally. It’s an ambitious, successful feat, and proof that strong synchronization is more than important—it can be dazzling.

Framing: Garbage, “I Think I’m Paranoid” (1998)

Close framing, particularly of human forms, can be a great way to increase your audience’s sense of intimacy with your subject. “I Think I’m Paranoid” uses this principle to great effect to create a shifting sense of closeness to singer Shirley Manson. Here, framing bounces from extremely tight, letterboxed footage of her mouth, to wider frames that show her aggressive, foot-pounding dancing, and neutral shots of the rest of the band.

It’s a perfect of way of putting the audience in the emotional state the song’s describing: the close shots feel extremely personal, invasive, and nervous, while the rest shows us her frenetic physical reactions to the emotion. As her lyrics imply, the video is “paranoid… manipulated,” and the audience feels it with every zoom and turn of the frame.

Visuals: Beastie Boys, “Sabotage” (1994)

A comedic visual story, “Sabotage” cast the Beastie Boys as tough cops in an homage to 1970’s police television like Baretta and Starsky and Hutch. The images are crucial to creating this visual story, especially since the lyrics are more of an analogue for the events onscreen than a direct reflection (the opposite of a video like Kanye’s “Jesus Walks”).

To that end, extreme attention was paid to costumes, sets, and action pieces meant to evoke the opening credits of the shows it referenced.

A legendary and influential parody, this video is a great example of dedication the principle of visuals and their primacy in messaging.

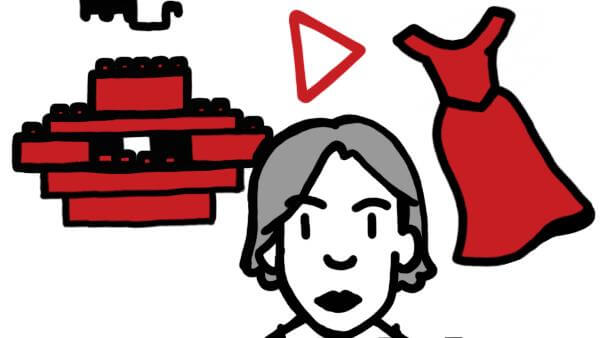

Geometry: The White Stripes, “Fell in Love with a Girl” (2002)

Long before The Lego Movie, there was “Fell in Love with a Girl.” All the visuals in this short, high-speed video are composed of Legos moving in stop-motion—from Jack and Meg White to mixing boards and more.

By simply arranging the Legos in recognizable configurations, the video gives the brain all the information it needs.

The brain stores memories in simple shapes and geometric forms for ease of recall, and this principle is on display for the entirety of the White Stripes’ rip-roaring ode to Jack’s rock ‘n’ roll crush. In one setup, the Legos tell the brain “drum set;” in another, the mind immediately recognizes “Jack’s guitar” or “Meg’s face.” The fact that Meg has no face when rendered in Lego is proof that the principle works, and works fast.

Human Forms/Hand Drawn: Swearing at Motorists, “Groundhog Day” (2014)

The principle of human forms is central to TruScribe’s use of the artist’s hand in our whiteboard videos: the brain is drawn to people and human shapes, and will focus on them whenever it sees them. In indie rock two-piece Swearing at Motorists’ “Groundhog Day,” the entire video is a close-up of a woman’s face and shoulders—and that’s about it. Occasionally, she mouths the lyrics sung by offscreen frontman Dave Doughman, but for the most part she simply looks into the camera.

The effect is magnetic.

With the minimalist guitar and drums putting the focus on the vocals, and tight framing keeping the audience close to the subject, engagement with the voiced lyrics and woman’s piercing eyes is total for the three-minute video. It’s simple and effective proof of concept: human forms are remarkably effective at holding our focus.

Color: Fiona Apple, “Paper Bag” (1999)

An accent color is not just a strong color, or a favorite in a scene. It’s a focal point, a way to direct the eye to the most important part of a frame and be sure that that image is retained as part of the video’s message. Fiona Apple simply but intelligently deploys an accent color in this principled way in “Paper Bag,” in which she sings a mournful tale of loneliness in a vintage café. She’s far from alone in the café, and her dance partners aren’t what you might expect for a song about sorrow and acceptance—they’re dozens of children, dressed in full 1940’s black suits, hats, and ties.

It’d be hard to focus on Apple except for one thing: her dress is the only thing in the video that’s bright red. This is how to keep an audience engaged with the central figure, even when adorable little dancers are everywhere around. Apple’s crimson attire signals the eye, and the brain, that while the rest of the participants are interesting, she is undoubtedly the star here.