Creativity has become sufficiently understood and celebrated that, looking back, it’s hard to imagine a time when it was considered unimportant. But pieces like Theodore Levitt’s 1963 article “Creativity is Not Enough,” provide a full-throated opposition to the value of creativity in business.

To let the fantasy-prone creative types have their way, Levitt insists, would lead to The End of All Things Good and Profitable. This includes dire and surreal warnings against letting creatives “make a fetish of their own illusions” (interpret that florid phrase how you will).

He compares creatives to grade-school age children, argues repeatedly that creatives never implement their ideas (with a few face-saving “maybe not all of them” disclaimers, of course). He deploys headers like “The Chronic Complainers” and “The Psychology of the ‘Creative Type.’” The article is 5,866 words long.

Words not included once in those nearly-six thousand: “women”, “she”, “her”, “diversity”, or “morale.” I suppose this kind of language would’ve only come to Levitt had he succumbed, even slightly, to what he calls “the particular disease of advocates of ‘brainstorming’” when determining his audience.

It’s probably not surprising that those who write on business trends and approaches have not, in the ensuing decades, decided that Levitt was onto something.

The debate now is about how much creativity is needed for business, and almost universally, the answer is “more.”

In 2018, Coutney Osborn referred to an IBM study that found 1,500 CEOs believed that creativity was the number one factor for future business success—above discipline, integrity, and vision. She outlines some reasons for this widespread agreement: better teamwork and bonding, higher rates of employee retention and attraction, improved morale, and increased workplace problem solving.

These aren’t fuzzy concepts, and they truly are not options or nice-to-haves: a disjointed and unhappy workforce that few want to join and that solves few problems cannot drive organizational success. Not for long, at any rate.

Duncan Wardle, former Head of Creativity and Innovation at The Walt Disney Company, speaks often on creativity, but not often about why your business should be creative.

In his words, “…I don’t broach this topic frequently because it feels so obvious: creativity isn’t a luxury, it’s a necessity! Whether you create magical children’s films and theme parks, or you do corporate accounting, creativity and innovative thinking are what allow your business to stand out from the competition and succeed.”

To undervalue creativity, Wardle contends, is to risk “…ignoring the warning signs that the status quo is about to shift” and find your organization “woefully unprepared for the twists and turns of the industry ahead.”

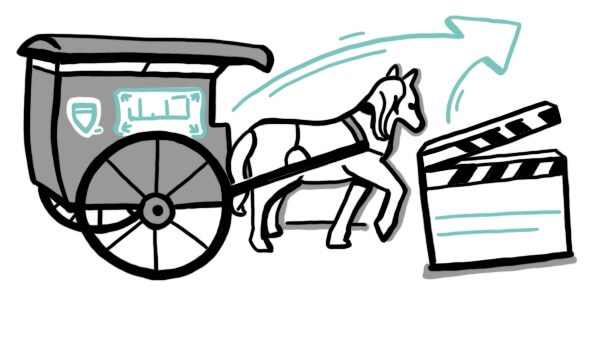

Using examples of the horse and carriage industry in 1890, marching in lockstep business-as-usual mode into obsolescence at the dawn of the automobile, and Hollywood’s attempts to scoff at Netflix, only to watch Netflix add as many subscribers in a year as it took HBO to accrue in forty, Wardle proves that a refusal to creatively anticipate, ideate, and change can bring quantifiable, significant losses.

Surely, though, there must be a middle-ground between pure creativity (Levitt’s waking nightmare) and a non-creative business (the bottomed-out carriage business)—and yes, there is, but it might not look quite the way you think it does.

While not encouraging steering employees away from their primary duties, creativity should encouraged at every level of business. All employees should feel free of limitations when it comes to creative ideation—because “companies that listen to creative ideas, wherever they come from, are the ones that usually succeed.”

“With business creativity, you get to solve problems faster and easier than ever before. It helps you discover unique ideas that will keep users interested and engaged,” write Anastasia Shch, and this, truly, is the point.

Creativity lets you ideate on moviemaking to circumvent Hollywood restrictions and become Netflix. It lets you be the company that sees the creativity of automobile makers on the rise and decide to follow this new direction instead of rejecting it—and thrive.

Listening to your creative employee’s idea to move the designers’ suite from the front of the office to the dimmer, quieter room is how you improve morale and productivity.

It’s how you show individuals that they are not cogs in a machine: they are thinkers who contribute, and their ideas are welcome. And that show of interest, that welcoming attitude, is how you end up developing a new product that revolutionizes your offerings.

Obviously, if ideas aren’t acted upon, then it’s hard to see their potential benefits. But, as much as the pro-conformity, change-resistant mindset might insist, this is not a failure of creatives or creativity itself—it’s a failure of an organization to correctly analyze, prioritize, and ultimately monetize creativity in its employees.

History is littered with shuttered businesses, broken by a refusal to adapt. Creativity is not just a way to avoid being one of them. It is the only way. Doing things the same way forever, and insisting that everyone in your organization walk an identical path, day in and day out, will never (and can never) generate novel, future-facing practices and products.

If you dismiss an idea because it hasn’t been implemented yet, you can be sure of one thing: that idea will not be implemented. If you are afraid of creatives defying the norms of your industry, those norms will leave you behind as other organizations change them, and you stand still.

Creativity is not a nice-to-have, and it hasn’t been one for a very, very long time. It is a necessity. It is the path to ongoing success.