The idea of “good” visual storytelling can be approached from many angles, from how much it increases viewer engagement through how well the viewer retains the information after viewing the visual narrative.

There’s another metric, though, that follows close behind retention: action.

When it comes to social movements, visual storytelling needs to be retainable in a way that allows viewers to know and take the next steps.

Today, we examine the visual language of Black Lives Matter, and the power of images to convey messages of social justice both in 2020 and years past.

As Mark Speltz wrote for Time Magazine in 2016, “the most powerful and compelling…imagery stick[s] in our brains, forming a visual memory or imprint refreshed or strengthened with each successive encounter.” Drawing parallels between Black Lives Matter and Civil Rights era images, Speltz argues that they “serve many of the same roles.”

These roles are numerous, capturing “meetings, marches, and demonstrations [to] convey immediacy and inspire activism.” From these more uplifting images of community meetings and representations of solidarity to the disturbing, often violent of images of confrontation and conflict, the visual stories of social movements influence both activists and onlookers.

Images that Resonate

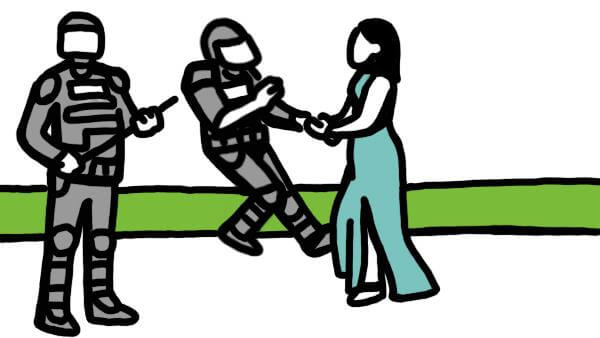

This image of Ieshia Evans exemplifies the ability of a visual story to wordlessly resonate with viewers both inside and outside the movement. The image shows two white police officers in full body armor and riot helmets running up to Evans to arrest her as she stands still and expressionless in the street. Behind the police in the far left is a phalanx of similarly armored police; Evans is alone.

This image becomes a visual story immediately—the story of unnecessary, aggressive policing against a solitary, calm protester. The speed of movement shown in one officer’s bent leg implies that the officers ran towards Evans to arrest her, while her stillness and unruffled dress (and the fact that she’s facing them) shows her total lack of fear.

To Black Lives Matters activists, there’s no question as to which of the parties is behaving reasonably—and to outsiders, the message is equally clear. This is a visual story of a solitary hero being confronted with two unjustified challenges.

This 1967 image of a child hurrying down the streets, hands in the air, pursued by a line of armed National Guardsmen, tells a very similar story. So does this one of peaceful marchers walking past riflemen from 1968.

Why are these single-frame, often text-free images so effective? The human brain prioritizes what it sees over almost all other sensory information—and to invoke the cliché, seeing is believing. A written article on police injustice might convince some, but it’s hard to find any people who can view American police using zip ties and brandishing bayonetted weapons at unarmed civilians and not recognize the injustice.

In other words, it’s vastly more difficult to spin an image. But what else does visual storytelling do for a social movement like Black Lives Matter?

Visual storytelling is wonderfully participatory medium, allowing people with skillsets from writing to drawing to photography and more to contribute to the movement. Even if the visual storyteller is not as directly involved as Ieshia Evans, they can still participate.

Art that Connects

Take a look at some of the art from graphic designers around the world, celebrating the life of George Floyd and elevating the Black Lives Matter message of equality. In particular, note this image by Quentin Monge.

Its simple depiction of a white and black figure embracing over the words “black lives matter” tells a story of togetherness. The human figures draw our eyes, as the brain always focuses on human shapes. Their simplicity and interconnectedness make them easily and quickly understood, and their fullness in the frame ensures that nothing else but the slogan below them will draw the eye. The slogan, of course, is the point.

Visual stories like this convey a different message than those of conflict, but serve the same purpose: remind Black Lives Matter activists of the importance of their work, and invite non-activists to see the movement’s message objectively. Put differently, it takes hard, bad-faith cognitive work to draw another message out of the love in Monge’s story, or to see the militarized police as somehow behaving appropriately.

There’s another reason that visual storytelling’s importance cannot be downplayed, both in and out of social movements: message accessibility for the hearing-impaired. “Deaf people are a part of this revolution also,” American Sign Language interpreter Rorri Burton explains in this insightful video.

Burton articulates the visual storytelling that dovetails with sign language, specifically the kinds of signs that have emerged to tell the story of police injustice, the life and murder of George Floyd, and more. She describes how “white” and “black” have different signs that are used by Black communicators, born out of the scenario and the need to create community.

The deaf experience of social activism is often an unconsidered one, but it’s a perfect example of visual storytelling conveying a vital message and forming the visual memory Speltz described. Presenter Benjamin Bahan proves the efficacy of gesturing in communication by telling a hearing audience a full narrative through signs—and correctly guessing that the audience understood.

Visual storytelling can take many forms, from carried signs, photographs, and designs to the sign language revitalized to tell a clear story to a community that even some in the movement might accidentally overlook. It’s a way of capturing a moment that, free of commentary, stands alone to have its message retained without confusion.

Generating a visual language is not just a strong way to gain engagement and retention—it’s a way to do both of those things within a community or social movement that drives solidarity and tenacity. It also shows the non-participating world what they need to see: a message of social justice, rooted in unfiltered visuals, that might change the minds of those who see and retain it.